Back during our early days as an Analyst with a venture capital fund, one of the Managing Partners always asked a simple question when assessing opportunities:

“Will this change the practice of medicine?”

It’s a simple question, but when evaluating investment opportunities, it was a question that encapsulated a philosophy which we helped us separate the interesting opportunities from the less interesting opportunities. As that fund was focused on leaps in innovation, it was an effective framework to keep in mind.

We were reminded of this quote while reading this article about how CrossFit is aiming to change disrupt how healthcare is practiced today.

What is CrossFit?

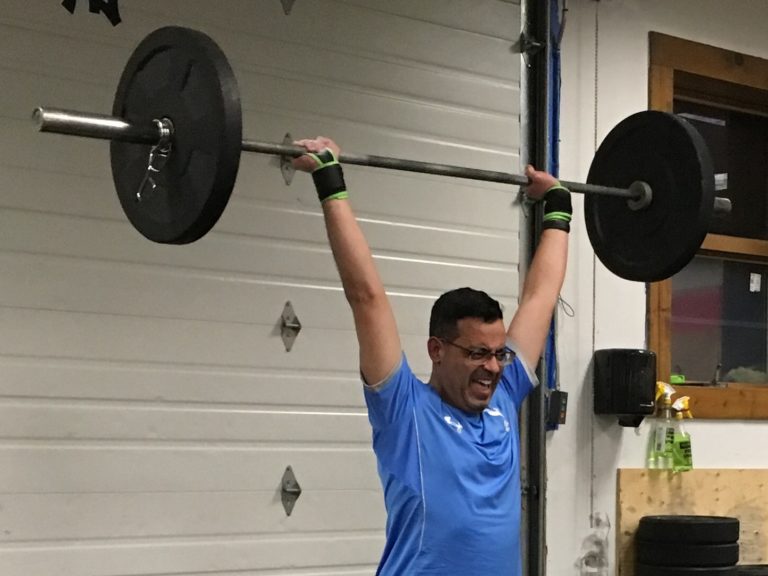

CrossFit is difficult to define. Essentially, it is a form of exercise involving a series of well-known movements, performed at high intensity, and usually at a heavy weight. CrossFit blends elements of weight lifting, gymnastics, running, cycling, rowing, aerobics, calisthenics…all in well-designed, short, intense workouts.

Can CrossFit Disrupt Healthcare?

Greg Glassman, the founder of CrossFit, is directly targeting the healthcare system. He is on a mission to tech practicing physicians not only about CrossFit as a fitness approach, but CrossFit as a way to treat and prevent disease, especially diabetes, obesity, and related conditions.

CrossFit created the MDL1 course, a program specifically designed for physicians to train them on CrossFit methodologies. Many of these physicians will not only open their own CrossFit gymnasia (or, “boxes”), but they will merge their medical practices and CrossFit boxes into a single, seamless health and wellness facility. This will enable physicians to blend nutritional advice, exercise, and, where needed, prescription and non-prescription medications.

This idea of physicians turning their practices into “wellness clinics” is nothing new. The challenge for physicians has been finding a way to implement “wellness” methods which a) their patients will actually use, b) which will result in a revenue stream for the practice that does not depend on insurance, and c) that is based on sound health and nutritional practices.

This is where CrossFit is different. As we see it, there are three characteristics of CrossFit which make it a viable approach for physicians (and their patients) who want to move their practices in this direction.

First, CrossFit exercise regimens are highly scalable and customizable. Each workout is adjusted to the strengths and weaknesses of the client/patient. So both the fit and not-so-fit can actually perform the same exercises at different scales during the same workout, with both benefitting from the effort.

Second, as the article points out, there is a tremendous sense of community in the CrossFit world. Each workout is performed in a group of 10-15 people. Mutual support is highly encouraged, thereby turning intense exercise from a solitary activity to a communal activity. Indeed, it is common for CrossFit aficionados to “drop in” to other CrossFit boxes while traveling. Acceptance is immediate, and judgement is non-existent.

Third, CrossFit recognizes that exercise alone is not enough. Nutrition, especially the elimination of processed foods and excessive sugars, is critical for long-term health. The advice is simple, straightforward, and one which physicians can easily dispense as part of their practice.

The Jig Is Up

For the past decade or so (perhaps coinciding with the genericization of statins), our industry has quickly moved away from developing drugs for largely preventable conditions. Yes, we recognize there are many exceptions. But, research programs in obesity and diabetes are being replaced by investments in programs for rare/orphan diseases, cancer, and diseases of aging.

And who can blame the industry for these decisions? Take Type II diabetes as an example. This is a preventable condition, highly genericized, and treatable with non-pharmacologic approaches (diet and exercise) if diagnosed early enough.

But what is the physician to do when she/he has been trained to prescribe statins and follow the established “elevated LDL-C leads to heart disease” dogma? Especially when this dogma does nothing to actually cure the underlying disease? And when training in nutrition in medical school is minimal or non-existent?

Isn’t that why physicians became physicians in the first place?

This is where CrossFit comes in.

Now the family physician can do more than say “Cut back on the French Fries and go for a walk, or else I will prescribe a statin.”

Instead, the treatment could be “I will ask the Manager of my CrossFit box (which is right next door) to give you a tour and tell you about how CrossFit can help you prevent diabetes.”

Interestingly, physicians also recognize that diseases of aging, such as Alzheimer’s, could be delayed with vigorous exercise. For example, a 2-year long study in Finland showed that blend of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and intense monitoring could prevent cognitive decline.

Coincidentally, there are now retrospective studies suggesting that the link between elevated LDL-C and cardiovascular disease is non-existent. Indeed, some authors are now suggesting that this link is largely based on “…fraudulent reviews of the literature.”

Other studies are questioning the link between dietary fat and heart disease. Meanwhile, gym memberships continue to climb, while we concurrently spend billions of dollars to treat diabetes. Is this any way to practice medicine?

Indeed, this places physicians in a tremendously difficult position. Do they follow established dogma (and avoid malpractice lawsuits)? Or, is there a diet and exercise philosophy and approach that is scalable, communal, and effective? And, which can be bolted onto an existing medical practice?

Given the long waiting list for the CrossFit MDL1 physician training course, there are many physicians who believe there is a viable alternative.

Is There a Role for Other Health Care Practitioners?

What about Pharmacists? Nurses? Nurse Practitioners? Physical Therapists? Will they also be impacted by these trends?

To some degree, all practitioners could be affected by these trends. For example, pharmacists are concurrently battling for their existence against automation.

But robots cannot easily replace the personal touch needed when patients need consultations about their medications, especially when their treatment regimens are complex due to concurrent illnesses or other reasons.

How about a consultative pharmacist as part of this clinic? It’s not unreasonable.

Will Insurance Cover CrossFit?

Interesting question.

Some insurance plans and employers provide gym membership benefits. Some cover the membership, while some reimburse membership fees upon demonstration of attendance. A brief search resulted in a few examples:

Presbyterian Health – Free access to thousands of national, regional, and local fitness centers, including group exercise classes.

Cigna – Healthy Rewards(r) program provides discounted rates on health and fitness memberships.

United Healthcare – Reimburses members $20 for every month in which 12 gym visits were performed.

But a key element that is missing is the motivation and discipline to go to the gym, which is not easy. Can physicians play a role in convincing patients to participate in a communal program like CrossFit? Possibly.

We believe this becomes much more likely when a) insurance coverage/ reimbursement is better, and b) when the gym is physically located alongside the physicians office.

Will CrossFit Change The Practice of Medicine?

It’s clearly too early to answer this question. It may take decades for the medical establishment to shift from the treatment of preventable diseases to the actual prevention of preventable diseases.

Perhaps the day will come when physicians will prescribe fewer statins, fewer NMDA antagonists, and fewer calcium channel blockers; replacing these with positive, communal workouts involving thrusters, pull-ups, and rope jumping.

However, we clearly have a confluence of factors which is making this shift plausible in the long run:

- Challenging practice economics/reimbursement, and need for complimentary revenue streams.

- Emerging doubts about the links between low fat diet and disease

- Unattractiveness of traditional exercise centers due to a lack of community, lack of guidance, fear of judgement, etc.

- Recognition that exercise has both health and cosmetic benefits which are achievable thought a communal, guided approach.

- Desire by many physicians to go beyond the “Do no harm” mentality and take a more proactive (non-pharmacological) approach and make a real impact in preventing and treating disease.