Seems like a simple question, right?

Ask yourself the question, then ask one of your colleagues the same question.

How much overlap is there? How much disagreement is there?

The confidentiality of data is one of those vague ideas that everyone claims to understand and recognize when they see it but cannot actually describe.

One way to think about the confidentiality data is to examine what the FDA publishes on its web site and in package inserts.

For example, a clinical trial result may or may not be confidential (depending on the context), but a precise formulation is always confidential.

A chemical structure is confidential up until the time the label is published. Patents may disclose families of compounds, but it is often difficult to choose exactly which published structure is the candidate under development.

Perhaps a better way to think about this question is as a process, instead of a yes/no answer. In other words, the question is not, “Is this specific piece of data confidential?”

Instead, the question should be, “What kinds of data do we disclose at which point in the process?”

Let's talk about process

For out-licensing, we prepare and use a series of three presentations with increasing amounts of data:

First is the Conference Deck, or Meeting Deck. This is a very short (10 slides or less) presentation to be used in a partnering meeting or video conference (or even a web site). Due to its short length, there is little room for data. Indeed, we assume that there will not be enough time to go through every single slide.

Which data go into this presentation?

We tend to choose one or two data points which the following characteristics:

- Experimental results (not design)

- A single result justifying the stage of development claim (i.e., Phase II clinical result for a Phase II candidate)

- Explainable quickly and verbally with a simple graphic and minimal text

- Data which clearly indicate the presence of more data

Note that the experimental result presented in this document has made the leap into the realm of non-confidential (public) data. Even if the file is not uploaded into a conference partnering system, displaying that piece of information in public is akin to publishing, and hence is no longer confidential.

This is precisely why we focus on a result, and not on the design. An experimental design may be unique, or utilize unique methods, reagents, animal models, etc. These “How did you do that?” kinds of questions should be reserved for post-CDA discussions and data rooms.

The second presentation is what we call the Follow Up Deck. It is a more detailed version of the Meeting Deck (around 30 slides), and is the file that is emailed to a prospective partner after a meeting.

As it is more detailed, it will have more data.

But again, which data are selected for this non-confidential presentation?

Obviously, whatever was presented in the Meeting Deck can be expanded upon in this presentation. Indeed, we recommend repeating and expanding on the point made during the meeting. But, again, the focus should be on the results, not the experimental design behind the data.

The Meeting Deck described previously is not designed to be emailed and read. It is meant to be displayed and used as a series of verbal cues during a conversation.

The Follow Up Deck is a different matter. It is meant to be read, although excessive text in a presentation format is annoying.

Once it is emailed, you must assume it will be distributed broadly, both internally and outside the recipient’s company (i.e., to consultants). So caution is advised when considering what will be included in this document.

What should be included?

Here are a few guidelines, keeping in mind that the objective of this document is to move the reader towards a confidentiality agreement:

- Repeat and expand on the data shown in the Meeting Deck. We recommend repeating that exact same slide, then following it with more detail. Why repeat? Because the repetition establishes a base of familiarity for the reader to move forward. Expand by focusing on results, minimizing the disclosure of experimental details.

- If the candidate has potential in multiple indications, there should be data supporting this claim. If a standard Preclinical model is being used, it should be noted. Comparisons versus established competitors, even in Preclinical models, is usually helpful.

- Justification for where the candidate will fit in the current treatment paradigm (and the corresponding projected patient capture) can be very useful. It is entirely possible that the reader will argue against your assumptions, especially the corresponding patient capture assumption. However, this is leading towards discussions on market potential and valuation, which will hopefully come later.

- Anything that is already in the public domain, such as an awarded patent, can be included, to the extent that it is necessary. For example, if an awarded patent describes a family of compounds, it is perfectly acceptable to list the patent number in the presentation. However, we recommend not identifying the specific compound that is discussed in the presentation until later in the process, if possible. This is why many companies use one nomenclature in patents and another in internal documents.

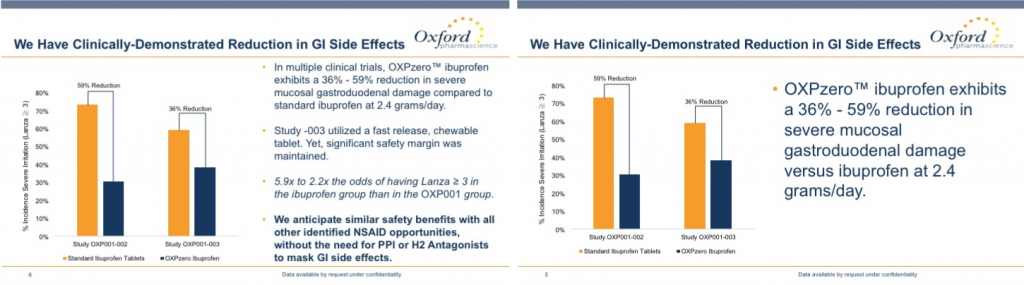

Same data…different slide formats. The one on the left is fine for Follow Up, but it has too much text for live presentation at a conference or webinar. For the latter, cut down on the text so that it resembles something like the slide on the right.

Same data…different slide formats. The one on the left is fine for Follow Up, but it has too much text for live presentation at a conference or webinar. For the latter, cut down on the text so that it resembles something like the slide on the right.

What's missing?

Again, here are a few suggestions of items which are not necessary:

- Pictures and details of buildings, labs, offices, and management. In fact, there is no need to provide management biographies until the very end of the document (if at all). The data supporting the candidate’s potential is far more important than the people who oversaw or performed the experiments. This is even true for investor presentations, which are not the same thing (this may the subject of another post). Plus, the pictures will unnecessarily increase the file size. Note that management CVs should be included in the data room, even though they are not confidential.

Is this really necessary? Does this really add value to the presentation? Especially when it’s the second or third slide? What information is here that cannot be readily found elsewhere? Is the candidate better simply because of the team?

- Detailed facts and figures that the audience/recipient will already know. For example, if you are attempting to out-license an opioid-sparing pain reliever, do you really need to educate companies like Mundipharma or Grunenthal on the need to develop novel pain relievers with non-opioid effects? Or on the number of deaths from opioid mis-use? Or educate Lilly on diabetes prevalence and insulin pricing?

- General details about disease epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment paradigms. Yes, you should project where your therapy would fit in the treatment paradigm, but if your audience company is in your therapeutic area already, you can safely assume they know all about the disease in question. If not, they will pretend they know and look it up afterwards. Exceptions can be made for rare diseases.

Of course, these are just guidelines. Each situation will be different.

But what is hopefully clear is that the focus of these data should be on results, not experimental details, not management, and not generalities which the licensing audience will likely know already. Note this may differ for the investment community, who may need some education on these issues, as their level of expertise is harder to gauge in advance.

Standard experimental models can be briefly mentioned in footnotes or captions. Unpublished (unpatented) information should never be disclosed at this stage.

What do I do after a confidentiality agreement is signed?

And now, it is time for a quiz.

Which of the following approaches do you think is best after a confidentiality agreement is executed?

A. Send interested parties directly into the data room, with full access.

B. Send a confidential document (prose or presentation), then send to data room with full access.

C. Send a confidential document, then send into data room with partial access. Provide full access after a preliminary non-binding Term Sheet.

D. Send interested parties directly into the data room, with partial access. Provide full access after a preliminary non-binding Term Sheet.

The correct answer is C. But before we explain why this is the case, let us look at the other options.

A (immediate and full data room access) is a bad idea for two reasons.

First, even if the data room is impeccably organized and crystal clear, it may still be difficult for a first-time visitor to find precisely what s/he is looking for.

Remember, once a CDA is signed, it is likely that other colleagues will be brought into the process. The data room may be the first time interacting with your company and your candidate. Thus, a document which provides some guidance is a good idea.

Secondly, a guidance document provides you with the opportunity to address specific questions that the other party continues to ask.

For example, if your Follow Up presentation does not address drug formulation in detail, a confidential “guidance” document can provide additional data and point directly to the location in the data room where the relevant data can be found.

This makes it far faster and easier for the other party to find the answer they are seeking.

B (send confidential document, then provide full data room access) is not a bad choice.

If the confidential document is in presentation format, it should be the Follow Up deck, plus more details. Additionally, there should be footnotes which clearly state where in the data room that piece of data would be found (hyperlinked, if possible).

Prose reports may also work well, provided they use data (identical graphics, etc.) from the presentations, and also with clear directions from the document to the source in the data room. Again, any questions which are pending should be directly addressed using confidential data.

The problem with choice B is that providing full data room access can be overwhelming. It’s best to provide enough for initial diligence, while gently prodding the other party towards a term sheet. What is provided after the term sheet will be discussed shortly.

Wait, are we suggesting that the confidential document begins with a repetition of the non-confidential presentation?

Indeed, we are.

Again, the post-CDA audience will likely be different than the pre-CDA audience. Some will be seeing/reading your story for the first time after the CDA is signed.

D (send directly to data room with partial access; full access after Term Sheet) is similar to B, but without the confidential guidance document. Again, we fully endorse the idea of guiding interested parties towards and through the data room.

So the answer is C. The confidential document provides guidance, while partial access provides an incentive to move forward to Term Sheet.

But what information should be disclosed pre- and post- Term Sheet?

Again, there are no hard and fast rules.

Certainly, things such as patent applications (especially ones which name and key chemical structures, unique processes, etc.) should be kept confidential for as long as possible.

If you have multiple clinical studies, i.e., 3-4 clinical studies in the same indication, we generally advise only disclosing one or two during the pre-Term Sheet stage, then disclose the others later (with clear indications that more clinical data is available).

Experimental methods should obviously be in the data room. These are a good example of the kinds of data which may need some guidance in order to be found quickly.

When faced with multiple reports describing a variety of Preclinical studies, finding one particular study design and result can be burdensome for the counterparty. Make it easy for them by telling them where (specifically) that information can be found.

And when we say “where” we do not simply mean “Folder ABC.” Rather, the direction should be explicit, i.e., Data Room / Preclinical / Folder ABC / Subfolder DEF / Report 123 / pages 38-42.

Information which can aid the other party with their commercial and reimbursement assessment should definitely be disclosed early in the process (post-CDA/pre-Term Sheet).

Data such as physician surveys, payer interviews, and the like could expedite their assessment, assuming these are truly independent, reputable sources of data gathering and analysis. It is unlikely they will use this information as is, but it could help confirm some of their own sources.

Note that your own internal valuation should not be in the data room at all.

So, what is confidential?

This is still not a straightforward question to answer.

But perhaps a more important question is, “How much data should I disclose at this particular stage of the process?”

If out licensing is thought of as a process, then a gradual disclosure approach provides opportunities to guide counterparties through the large amounts of data, without overwhelming them with data that may be difficult to find.

Generally speaking, the more advanced the candidate, the more of an emphasis should be made on presenting the latest data pre-and post-CDA, while saving some Preclinical (i.e., GLP tox work) and Phase I details until later in the process.

Keeping critical trade secrets confidential until the end of the process is prudent, recognizing that enough confidential and non-confidential information must be supplied in order for a solid preliminary assessment by your counterparty.

Making it easy for them will separate you from your competitors seeking that one license you and your investors want.

Looking for a low cost, secure data room option?

Check out the VISTX DataCloud.

The VISTX DataCloud was built from the ground up to provide a low-cost, fully functional, secure data room.

Forget spending $10,000 a month…you can get the VISTX DataCloud for the Starter price of $495 per year…yes, that’s per year, not per month.

We love the DataCloud, and you will too.

Simply click on this link to watch the introductory video and ask for a quotation.