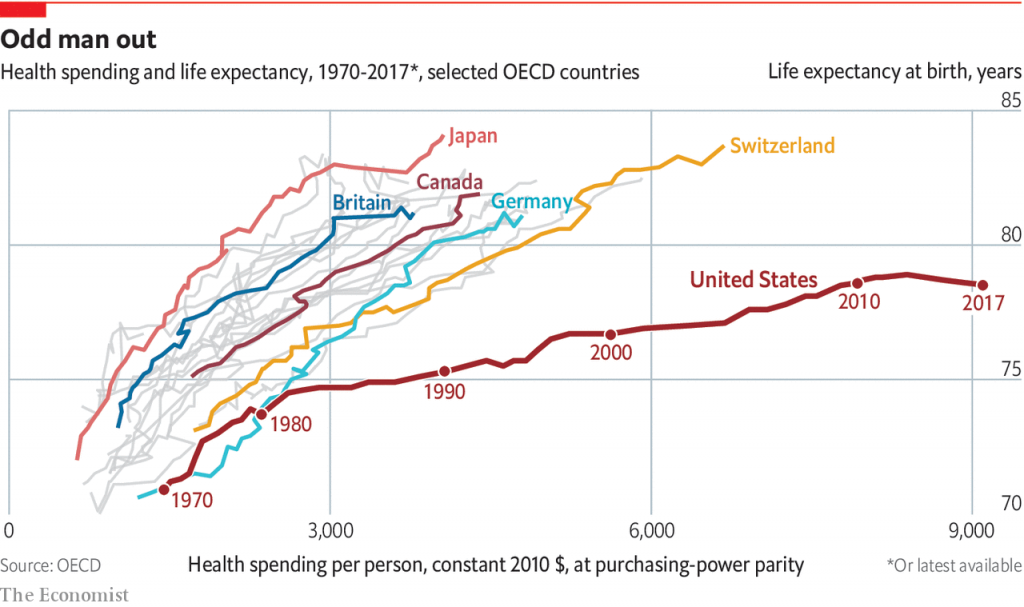

Undoubtably many of you have seen this graphic as it has made the rounds.

Indeed, there are reasons to be concerned.

Flat to declining life expectancy in a country like the United States is unanticipated, and unacceptable in any country.

Yet, our life expectancy has not increased much beyond the ~75 years as measured in the 1990s, especially when you compare that slope to those for other countries.

So what is going on? Or, what happened in the 80s and 90s in the US that did not happen elsewhere?

We refer you to an excellent article published last year on this very question.

The key observations from that article include:

1. The US lacks a national approach to healthcare spending. Our free market approach means prices for healthcare (and not just drugs) can and do skyrocket relative to other countries.

2. Increased consumption of medical care. Now this is a tricky one, as it implies that the US has an inherently unhealthier population. But with many insurance plans having generous co-pays, some consumers may be driving medical expenses for minor or even unnecessary reasons.

3. Expensive innovation, and no, we don’t simply mean expensive drugs. For example, coronary artery bypass surgery came into vogue during this time period. It became very popular…and is very expensive.

4. Even if you back out deaths caused by vehicular accidents, firearms, drugs, etc., etc., the US data look pretty much the same relative to other countries. So that’s not the cause.

Several authors have noted that the divergence seems to coincide with decreased spending on social and educational programs, especially for low income households.

As a Brookings Institute has noted, the US spends too much on health care and too little on social care:

The data from Brookings suggest that increased “social care” spending, i.e., education on healthy eating and other habits, can prevent or delay future healthcare spending. Conceptually, this makes complete sense. But whether increased (and early) social care spending correlates directly with reduced health care spending later in life is unclear.

Of course, data like these will attract comments blaming rising drug costs. Recent headlines and stories describing the “most expensive drug ever approved” are no help. Indeed, they provide fodder for ignorant comments which are not worth repeating (usually from politicians or lazy journalists).

The reality is that drug spending increased ~2% in 2018…certainly not “skyrocketing” by any standard.

Meanwhile, the drivers of healthcare spending are far more complex. For example, many analysts have noted that healthcare in the US requires “…more, and more highly paid, people to deliver care” Whether this is the case in other countries is unknown.

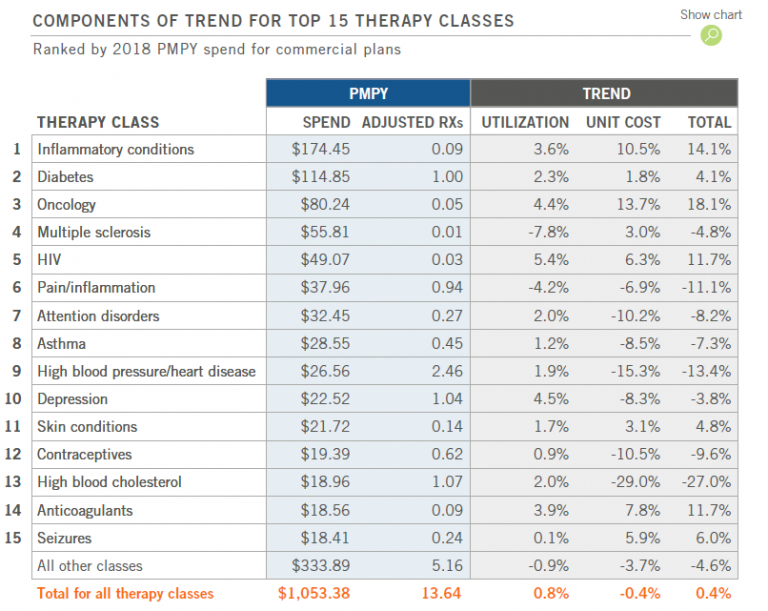

A more interesting way to look at drug spending is by therapeutic area. In a post from May of this year. Adam Fein reproduced a table from Express Scripts, which we reproduce below:

The therapeutic areas are listed according to PMPY Spend.

However, it is useful to look both at spending AND trends. For example, Express Scripts is spending the most on drugs for “Inflammatory Conditions” and this is being driven by increases in both utilization and costs.

As you scan the list, it’s important to ask an important question.

Which of these therapeutic areas are driven by indications which are preventable?

This is key because prevention can be driven by education, coupled with self-discipline and family/social support.

Let’s take the second entry: Diabetes.

We do not know how much of this is for Type I versus Type II. But, we do know that many cases of Type II diabetes can be completely avoided and even reversed through proper diet and exercise.

Similarly, how much hypertension/heart disease can be avoided completely through education, prevention, and non-medical (lifestyle) approaches? Same for high blood cholesterol?

Indeed, cholesterol is a troubling one because of rapidly dropping drug prices and increased utilization. That is exactly what we do not want.

There is an argument to be made that utilization growth is a positive trend if the drug spending helps avoid other, more expensive spending, like hospital stays. So cheap, effective drugs that can prevent hospitalization are worth every penny in the long run…but only if they are effective (cf., antibiotics)

By the way, it has not escaped our notice that total utilization increased by <1%, and unit cost declined by 0.4%.

Skyrocketing…indeed.

I might succumb to Alzheimer’s, cancer, a drug-resistant infection, or an accident. But I am unlikely to need expensive, end-stage renal disease care secondary to chronic, uncontrolled diabetes.

Social spending…education on diet and exercise…support…prevention…

We don’t hear politicians nor journalists talking much about this (and don’t get us started on the tactics used by “Big Food” to get us to eat more processed, cheap food substitutes).

Yet it is likely that more social spending is the key to both reducing overall health spending AND increasing life expectancy.

Ironically, falling drug prices are actually not helpful in this context.

Cheaper, safer drugs makes it all too easy for some physicians to quickly prescribe an easy fix to a problem (i.e., prediabetes) which actually requires a more complex, life-long solution.

Thus, we have the means to reverse these trends.

But do we have the individual and collective will to make the changes we need to make?